An Artist in Search of Meaning. Anton Reznikov on Doubt, Crisis, and the Possibility of a New Artistic Language. Part 1

Lesia Liubchenko

Interview conducted by Lesia Liubchenko, Content Lead of UFDA

This conversation with Anton Reznikov turned out to be unexpectedly expansive — it found room for reflections on time, for doubts, and for attempts to rethink the role of the artist in a world oversaturated with content. We talked for a long time — so long, in fact, that we decided to split the interview into two parts.

In this first part, we discuss teaching experience, the place of the artist in society during wartime, as well as the comic Near Mint and the vulnerable states from which art is born.

Lesia: First, I’d like to ask about your background, because there’s not much public information about your life journey. Could you please tell us whether you’ve been passionate about art since childhood, or was there a turning point that prompted you to pursue it?

Anton: That’s a good question, because I can’t really say when exactly I realized I could do something in the field of art. But, like all kids, I drew. I really liked drawing Ninja Turtles, RoboCops, Batmans, and so on. I had a certain status as an artist, and the bullies didn’t mess with me because I had carved out my niche in the class, and people were always asking me to draw something. During lessons, I usually didn’t listen — I’d just sit at the back of the class and draw.

My mom often traveled to Germany and would bring back books published by Taschen about famous artists for me and my brother. I would take these books to school, sit at the back, and draw portraits of artists like Cézanne, Manet, Monet, and Picasso. And the teachers really liked it.

But I think the real breakthrough in my art creativity (I don’t like the word creativity, but I don’t know a better one) happened in 2008, when I started studying with Yevhen Bykov, a renowned artist from Kharkiv (I’m from Kharkiv myself). Before that, I was taking lessons from an artist named Vadym. He saw that I was talented and advised my father to take me and my brother to study with Bykov. That’s where I met his student, Mykola Kolomiiets. It was with him that I really began to work (since Bykov was already at an age where he couldn’t fully work with students), and that’s when I started seriously moving toward art. I mean real art, not just sketching portraits at the back of class, but professionally.

By the way, when Bykov was considering accepting me into his studio, I showed him those portraits. He liked them and decided to give me a chance.

Lesia: In your opinion, do artists need formal education? Or can they develop on their own? What was your experience?

Anton: I studied at the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts. But it was complete nonsense. I don’t know what it’s like now, but I’m pretty sure nothing has changed — maybe it’s even worse. The main problem with that academy was that it was stuck in Soviet times; almost all the teachers were very old.

I believe the main purpose of any university, especially an arts institution, is to introduce a person to reality, to give them the opportunity to work in the real world, taking into account contemporary needs. That simply didn’t exist at my academy. We were stewing in this soup of the Soviet approach to art — academic drawing, dull painting, models draped in fabrics of a puke-colored hue. It had nothing to do with the present day.

Who needs academic painting now, those traditional compositions? It’s no longer relevant. But at the academy, that was still considered relevant, and everyone was trying to master academic drawing and portraiture, without any understanding of the time we were living in. It was a swamp — like a bubble that lets nothing in from the outside, only stews in its own juices.

I believe the primary goal of an academy should be to introduce a person to the real professional world.

And that goal wasn’t achieved at all. What’s done is done. And if we’re talking about the academy I studied at, I don’t think anything will change. It needs serious investment and renovation — the studios are in terrible condition. A lot needs to be done, and it’s unlikely anyone will actually do it.

Lesia: Your brother Leonid is also an artist. Do you influence each other creatively? Do you perhaps learn something from him, or he from you? Or is it the opposite — do you compete?

Anton: We studied together in Bykov’s studio. Honestly, for a while, I felt like my brother was doing better than I was. I could see it in the reactions of people like Mykola Kolomiiets, our…

Lesia: Mentor…

Anton: Yeah. That annoyed me, and I tried to do better. So yes, there was competition. I tried to borrow some of his techniques. I don’t know what my brother would say about that — everyone sees things in their own way. But I looked at his work (it was really cool) and wanted to do even better. You could say it was a form of interaction. I forgot what it's called... a challenge.

Lesia: Someone challenges you, and you try to outdo them.

Anton: That’s a great motivator — because how do you work when there’s no challenge? How do you get better? That’s what I believed then, and I still believe it now. Stability.

Lesia: Would you say that comics have become your form of self-expression?

Anton: No, I wouldn’t say that. I started to appreciate comics as an art form after working with Borys Filonenko and Danylo Shtangeiev on the comic Near Mint. Before that, I wasn’t particularly interested. As a kid, I read superhero comics — but who didn’t love those? Well, maybe some people didn’t, but I did. Still, at that time, I didn’t have any particular view of comics as art.

Lesia: And before that, what formats did you mainly work in?

Anton: Paintings, drawings… I worked a lot in A4 format. What’s it called? Sketches?

Lesia: Sketches?

Anton: You could call them sketches only because of the small format, but they were actually fully developed graphic works. I also did paintings — classical art, so to speak.

Lesia: The academic kind you mentioned earlier?

Anton: No, I couldn’t stand that stuff. I was never good at it. I got very poor grades in academic drawing. I almost got expelled from the academy several times because of it. Unfortunately, I wasn’t expelled. But I didn’t care.

Lesia: By the way, your portfolio also includes 3D visualizations and designs for industrial enterprises. Do you consider such projects to be creative as well? Or do you need a special kind of inspiration to realize them? Though I’m not sure if you even like the word inspiration…

Anton: No, I don’t believe in it at all. I think what people call inspiration is actually a long period of thinking and gradually moving toward a goal. I’m always thinking about what to do, thinking about the idea, and I need time. That’s when inspiration comes. But it’s a process, not something sudden. It’s gradual work. Inspiration is the result of that work — it doesn’t just come out of nowhere. Though, of course, I can only speak from my own experience.

As for the 3D visualization, that was a commission from a Ukrainian engineering company. I wouldn’t say there was the inspiration — it was a job, and I tried to do it as well as possible. Though to this day, I still haven’t been paid for that project.

Lesia: But that was back in February 2024 — quite some time has passed.

Anton: Yes. Well, who knows… Anything can happen unexpectedly.

Lesia: You also work on book illustration. What do you enjoy most about that process?

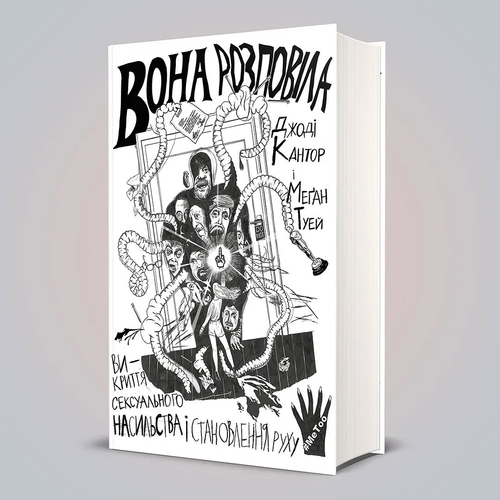

Anton: I did the cover for a book called She Said, about sexual violence against women by celebrities. It featured that well-known producer…

Lesia: Harvey Weinstein?

Anton: Right. I wouldn’t say I found it particularly interesting — it was more about wanting to make something as sharp and bold as possible. And I think I did. I read a review of the book that mentioned the cover, saying the artist did exactly what was needed — no compromises.

I could say it’s interesting to interpret a literary author visually, but in this case, I was just interested in creating something provocative. And I think I pulled it off. But I wouldn’t say I have extensive experience illustrating books. Back in the academy, I did illustrations for my favorite works or favorite authors as part of assignments. But that was more like playing around.

Lesia: Or, on the contrary — learning, training.

Anton: Well, yes, yes.

Lesia: You taught for a long time at the Aza Nizi Maza art studio in Kharkiv. How did that experience influence you and your artistic practice?

Anton: That studio was founded by Mykola Kolomiiets. After I graduated from the academy, he invited me to work with him there. At first, I worked as his assistant, and later I had my own group of kids and even my own assistant. I worked there for six years, and those were the best years of my artistic life. It was there that I became who I am.

Lesia: In one of your interviews, you said you see yourself as someone who guides and mentors. Why is that role important to you?

Anton: That’s what I believed back then. Now, not so much. But when I worked with children, I sincerely felt that I was passing on experience. There was also another important reason I loved working with kids: I drew inspiration from them (even though I don’t really like that word). I was always amazed at how freely they worked with form and how they found ways to express things that I could never have come up with on my own. So I actually copied a lot from the kids and used their visual and conceptual approaches in my own work. And I think that’s exactly how it should be — always looking for where you can take something for yourself.

I found that in working with children, I gave something, but I got a lot in return. It was more of a collaboration than a typical teacher-student relationship. The kids loved me, and I loved them. I enjoyed watching what they created. I learned more from them than they did from me.

I think the main goal of a teacher is to provide acceleration, to give a push, to awaken in the person you’re working with a desire to find an interesting solution to a given challenge. That’s the most important thing — to inspire.

Lesia: And there’s that word inspiration again.

Anton: Honestly, I can't really say I taught the kids, because, as I’ve already mentioned, I had terrible grades in academic drawing. I didn’t teach in the classical sense of the word, and no one in that studio did. What we did was help children discover their talents, offer them technical tools to realize their ideas, and help transform their visions into complete works that could be exhibited and shown to an audience. That was the main task — not to teach drawing, but to unlock talent and give it form. Because talent without form — while not bad — simply isn’t enough.

The main goal of the studio was to transform children’s creativity into a full-fledged artistic statement, one that could compete with adult art — and sometimes even surpass it. Can I say I was a teacher in the classical sense? No. But I was a teacher in the sense of someone who gives a push, helps bring an idea to life technically, helps develop it and turn it into art.

I won’t say how well I managed to do that, or whether I managed at all, but that was my goal. And I believe that’s the main goal of any teacher.

Lesia: You speak about the studio with such enthusiasm! Maybe you could recall the most emotionally intense moment from that time, something you’d like to share?

Anton: It wasn’t just the work — even simply being there was incredibly intense. I’d say we were like a family. That’s a good thing in one way, but also bad, because professional collaboration shouldn’t be like family relationships, and we didn’t have that separation. We could work all day and all night, then another day, then another night — just riding on some kind of high. It was exhausting, but it always felt like an adventure. That’s probably the best word to describe that experience. I can’t recall specific days or moments, but the whole experience was unforgettable.

Lesia: I’d love to talk about your collaboration with Borys Filonenko, whom we’ve already mentioned. How did you meet and start working together?

Anton: We first met back in 2012 during an exhibition at the YermilovCentre, where my brother and I presented a project — a wall of sketches. It was a collection of many drawings we had made over time, turned into a large installation. I remember Borys voted for that project. Unfortunately, it didn’t win, but that was our first encounter.

We actually got to know each other better later at the studio, when it moved to a new space. We were renovating and moving things in, and we met there. That’s when our friendship began. But not the collaboration — that came later, when we worked on the comic book In Mint (U m’yati). Borys and Danylo started it together, and then Borys invited me to join in to create the central section of the comic, the color part, and also the cover.

Aside from that, we worked on some group projects — posters, exhibitions, festivals — but all within the context of the studio.

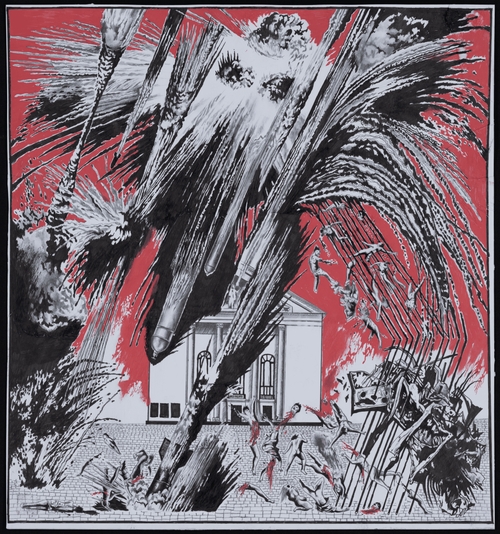

Lesia: Comics are often seen as an entertainment genre, but Near Mint is a deeply emotional, dramatic story. Did you feel, while working on it, any internal urge to challenge the stereotypes about comics?

Anton: Honestly, while I was working on my part of the comic, I didn’t even fully know what it was about — just the general idea. Of course, we had a lot of meetings and discussions, but I still didn’t have a complete vision of the whole thing. And I wasn’t particularly trying to get one, either, because I had the script for my section and a high level of freedom. I could change things in the script, suggest ideas.

There’s a moment in the comic where sheep are talking, and one says: “Look around — you won’t find any sympathy here.” I remember that line came from one evening when we were all sitting in the studio after a long day — Mykola, Borys, Danylo, me, and some others. I started complaining — like, “Ugh, today was so hard, the kids didn’t listen.” And then Mykola says, “Look at all these people. You won’t find any sympathy here.” Later, I suggested adding that line to my section of the comic and slightly reworked the storyline to include it.

Lesia: You’ve referred to Near Mint as a piece of “graphic poetry.” Where did that metaphor come from?

Anton: First of all, the drawing style itself evokes poetic imagery. I mean, it’s a light drawing — just clean linework. My part is more prosaic, since it’s filled with color, light, and shadow. But the section that Danylo did feels very poetic and airy to me, precisely because of its visual presentation.

Lesia: I also know that the comic was printed in Poland. How did the Polish audience receive it? Are there any plans to publish it in other countries?

Anton: Yes. I went to Oświęcim (Oświęcim is a town in southern Poland. It’s known for the Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau, a former WWII concentration camp) — by the way, that was my first experience being in a place like a concentration camp, and I was deeply moved by the atmosphere. We presented the comic there: I was physically present, and Borys and Danylo joined via Skype. The Polish people I spoke with during the trip were amazed. And the publishing house that printed our comic was as well.

I talked to the editor-in-chief, and he told me it was something incredible — that he even teared up while reading it. Honestly, I don’t know how the broader audience received the comic, but I’m certain it stands out from others and represents the best of comic culture in Ukraine right now. I don’t know if something better will come — I hope so, but I don’t know.

Lesia: Let’s hope so! Could you please tell us how the beginning of the full-scale invasion affected you and your art?

Anton: When it began, I was visiting a friend. The atmosphere the day before was very tense, and it was already clear that something was going to happen. At that point, I didn’t think it would be a full-on war, but something was definitely coming. On the night of February 23rd to 24th, I stayed over at my friend’s place, and I had a dream. In the dream, I heard the sound of explosions, and my character in the dream understood that it was war. Reality broke into the dream and made itself known. I woke up, my friend and I went out onto the balcony, saw explosions and lights far beyond the forest, and understood that the war had started.

Then we spent another week in a bomb shelter in Kharkiv. Looking back, I can say that those were the best times of my life. That’s when I truly felt alive and realized the value of life. When the threat is so close and so vast, some other inner mechanisms kick in. On one hand, there’s fear; on the other, I almost enjoyed that period. I even miss it a little now; I often remember that week as one of the most vivid and intense of my life. That was until I left for Lviv. Were you asking about how it affected my art?

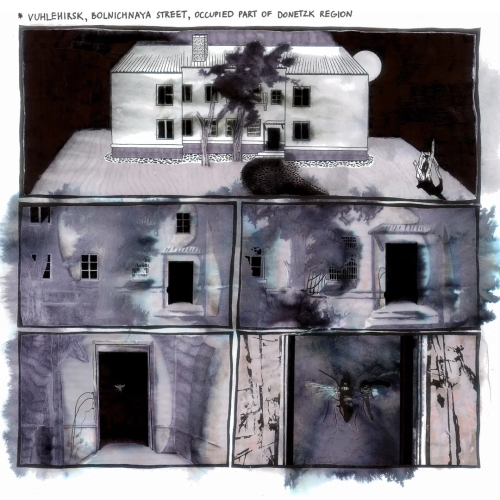

Lesia: Art and life. For example, your grandmother lives in Vuhlehirsk. That’s also occupied territory, since 2015.

Anton: The first project I did outside Ukraine was dedicated to my grandmother. It’s a project called “The Grandmother's Eyes.” And just a few days before the invasion began, on February 17th, it was her birthday. She called me on WhatsApp (she has very poor eyesight because she has glaucoma) and said that the only thing still holding her up is me and my brother, our images. Being abroad, I decided to create this project. The idea itself came to me while I was still in Ukraine, but I couldn’t manage to draw at that time. So, I completed it in Germany. I think it turned out well.

As for how the war has affected my creativity, honestly, I don’t really know. I haven’t made many projects dedicated to the war. And I can’t say it has had a positive impact on my creative process. I’m currently in a constant crisis. I don’t know why exactly, but the war has contributed a lot to me not even knowing what to talk about, what to say to this world. I don’t know what can be more emotional than the war itself. It’s a level that’s very hard to surpass. So, what can an artist say about it now?

What can one create that would be bigger than the war? Nothing. Because the war itself is so emotionally overwhelming that no visualization will work.

So right now, I don’t even know what to say through my art. The bar is very high.

Lesia: Let me move on to a less emotionally charged question. How do you see the role of art in the era of digital technologies? What kinds of influences might it face, and how relevant can it remain during this time?

Anton: Do you mean artificial intelligence?

Lesia: Yes, particularly that. How do you feel about its use in art? Is it a threat to the artist or, conversely, an opportunity for new forms of expression?

Anton: Artificial intelligence is, like everything else, just a tool. It all depends on how it’s used. So, I don’t see it as a threat. I hope AI can give art some kind of new impulse. Because honestly, art has already become deflated: everything has been done, everything has been said. And I don’t see many ways for humans to add something truly interesting and important anymore. But what AI can do—that’s interesting. How will it understand art?

I believe the time will come when AI itself will be the main artist. I’m curious to see how that will unfold.

As for the threat… Sorry, artists, we’re exhausted, we have nothing left to say, so step aside for it! I’m curious how the collaboration with AI will go. I hope it will open new ways of expression, because people are no longer capable of doing that themselves.

Lesia: Does the idea that artists have creatively exhausted themselves not discourage you too much?

Anton: It’s just a fact. I’m not saying there aren’t good artists. There are good artists, but are they capable of doing something truly important and great? By ‘great,’ I mean discovering a new path, like what was done in the 20th century. Pablo Picasso, for example, is the first who comes to mind. He opened new ways, but nowadays, I don’t think that’s possible. No figure can do that.

So, sorry artists, but we have a problem. You can make something beautiful, something very beautiful, but something that truly opens a new path… I have my doubts about that. However, maybe artificial intelligence will make that possible. Besides that, I’m also interested in whether art is even possible without emotions, without personal thoughts and perspectives. Because AI doesn’t have those.

Lesia: So basically, art without authorship?

Anton: Not exactly without authorship, but art without a human. We know art exists because of humans. But can we call what artificial intelligence will create (and I’m sure it will) art?

What happens if you remove the human from art? Will it still be art, or will it be some new level of art?

Or will it be something entirely different? Art without a point of view, without emotions — is that even possible? It will be interesting to see.

Lesia: Will such art find an adequate response among viewers, among audiences, if it lacks emotions, a message…

Anton: Of course. Will it even be art if there is no feedback from the audience? It seems to me that art has already said everything. And I don’t see how it can add anything else. And if the key ingredients of art disappear, will that be some new form of art? Or will it even be art at all? If not, it will be interesting to see what that looks like.

Lesia: Actually, my question about modern technologies and art in this era was a lead-in to a question about initiatives for preserving art through digitization. UFDA has digitized some of your works. How do you feel about such initiatives, and what interested you about participating in our project?

Anton: I feel very positive about it because it’s a reliable way to preserve culture in the digital age. The war itself can destroy cultural heritage. Even if that happens, at least there will be a digital copy of the work, and that’s not so easy to destroy. I don’t think war can destroy it. (Unless it’s total war, but that’s not the topic now. Although maybe total war could…).

I think it’s very important, and it increases the chances that works will remain in the digital world, regardless of war or other circumstances. It’s like a museum, but more reliable than a physical one. Because a physical museum can be destroyed. Goodbye, Leonardo da Vinci and all the others! A digital version of art is not so easy to destroy. I think this is good, and we should keep it that way!

Lesia: Which of your projects was the most difficult for you emotionally or technically, and why? I guess it’s “Hey, What’s Up”?

Anton: Oh, no!

Lesia: No? Then which one?

Anton: “Hey, What’s Up” — I made it during a residency in Ireland. I arrived and three days later got COVID-19. It was the second time, and I felt really bad. But I can’t say the project itself was difficult because of that. The hardest, emotionally, was the diptych I worked on earlier in the studio, “Wild Hunting,” because at that time, my grandmother was dying. She had cancer, was 84 years old, and it was my first encounter with death. No, I had seen death before — I saw people who were hanged because I spent a lot of time in my grandmother’s village as a child, and many things happened there. But experiencing the death of a close person was new to me (I really hope I won’t have to go through that again anytime soon). And it was exactly during that time that I was working on this project. It took only two weeks, but they were very difficult weeks. And when I finished the project, my grandmother passed away. Her death felt like a full stop to it. It’s hard to forget, so purely from an emotional perspective, it was the hardest.

From a technical point of view, the hardest project was the one I did with Yevhen Kogan, my friend, who also worked in the studio.

In December 2021, just before the war started, we were working in Kyiv at the office of the IT company “SupportYourApp.” Yevhen and I were creating a large wall — six meters long and four meters high — a half-bas-relief, half-painting. We worked for a whole month, every day, without breaks, from morning till evening, even into the night. By the end, I couldn’t even raise my hand because it felt frozen in the position I held it while working. I had very painful muscle spasms.

On the last day of work, my friend felt unwell. We were staying overnight at the office, and the next morning, the security guard came in. He walked into the room where we worked and where the piece still is, looked at us, and we were lying on the floor, covered with building materials, trying to sleep, like two barely alive homeless guys. It was quite funny. So purely from a physical point of view, this project was the hardest.

For six meters, we cut shapes from polystyrene foam, then plastered and painted everything — all during a month, every day, from morning till night. Very intense work, but also a very good time that I miss. I would really like to do something like that again, but unfortunately, there hasn’t been an opportunity so far.

Thank you for reading the first part of our interview with Anton Reznikov. To explore Anton’s works digitized by Digital Original for UFDA, visit his profile. Stay tuned for more!