An Artist in Search of Meaning. Anton Reznikov on Doubt, Crisis, and the Possibility of a New Artistic Language. Part 2

Lesia Liubchenko

Interview conducted by Lesia Liubchenko, Content Lead of UFDA

We’re back with part two of our conversation with Anton Reznikov. This time, we dive into his visit to Francis Bacon’s studio, talk about disillusionment and a crisis of vision, explore art beyond the human figure, and look at how to find new meanings in a rapidly changing world. Missed part one? You can read it at the link.

Lesia: In your works presented at UFDA, I noticed botanical, phantasmagoric, and cosmic motifs. At the same time, you create comics with entirely real people and real experiences. Has this kind of dualism always been present in your art? Or was there something that came before it?

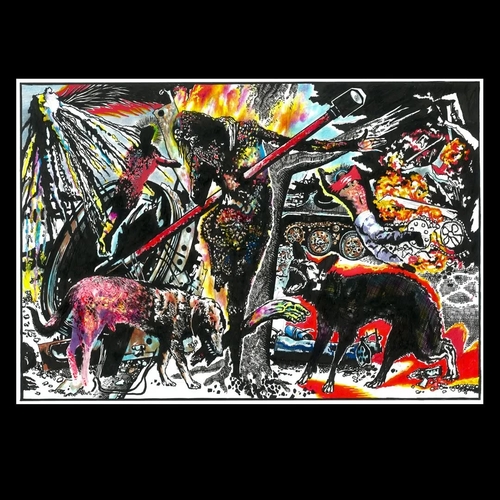

Anton: The comic “In the Mint” was, in a sense, a commission for me: there was a plot, a script. I worked based on that, not really thinking about the fact that I had quite a lot of freedom when it came to the visual side, which I designed myself. We finalized it with Borys, but the style was my suggestion. As for many of the drawings in your collection—like the flowers, animals... In fact, those are sketches for a video game that we were developing with Yevhenii, his brother, and my brother. We had a small four-person team, and we were creating a game. These particular drawings are sketches of its characters. So, those images were dictated by the game’s concept, as it was about phantasmagoric entities. Interestingly, the previously mentioned project for SupportYourArt was actually based on a sketch for that game. I thought it could be turned into a large-scale piece. I proposed it to the company, and they agreed. They gave us a budget, and we made it happen.

Lesia: And what happened to the game? In the end, were you able to finish it or not?

Anton: Nothing happened — we didn’t make it, partly because of the war, as we ended up in different places. But as a result, the world received many “interesting” examples of my work. And a huge wall in Kyiv.

Lesia: On your Instagram, there’s a post about your visit to Francis Bacon’s studio. Can you tell us when that happened, what you felt at the time, and what you like about this artist?

Anton: I’ve been there twice. The first time was in 2022, when I came to Ireland for an artist residency. I flew into Dublin and had some free time. Of course, I decided to go see the studio. It’s located in a museum — essentially a room within a room. I had seen many photos of Bacon’s studio back when he was still working there. And everything was just like in those pictures: books, shoes — all piled up in the space. I was in shock because this was the place where one of the most important postwar artists created his work.

For me, it was a very unusual experience, because I saw the place where masterpieces were made.

It was fascinating to see his things — brushes, palettes, rags, easels — all smeared with paint. By the way, there was unfinished work there. It was at the sketch stage: just a drawing without any continuation. It was really interesting to see the initial phase of how Francis Bacon created his paintings. I also really liked his notes drawn directly on the walls: measurements, small sketches.

For me, it was a very unusual experience, because I saw the place where masterpieces were made. You’re standing next to his personal belongings — you can’t touch them, but you can see them right there. It made a huge impression on me. There was also Francis Bacon’s desk available for public access. It wasn’t…

Lesia: It wasn’t sectioned off.

Anton: Right. It wasn’t part of the studio itself, but of his home in general, so it was placed outside the main space. And you could actually touch it. I even saw cup stains on it. In several interview videos with Bacon, he’s sitting at that table, and there’s a tea or coffee set there. The distinctive ring marks from the cups were still visible. I touched that table very carefully, imagining how Bacon sat there, had tea, ate breakfast… It was a very immersive experience. Because seeing his artworks is one thing, but being in the place where they were made — that’s something else entirely. It was deeply emotional for me.Ф

Lesia: So it’s a kind of museum of the artist’s state — the environment he created in. It turns out that through the space, you can better understand his life and art.

Anton: Yes and no. For example, in all the photos of him in the studio, he’s always wearing a neat suit and shoes. When you see a person not in work clothes, standing in that chaos and paint-splattered mess, it’s fascinating.

Lesia: Maybe it was just for the photos?

Anton: Something tells me he actually worked in those clothes. I don’t know why, but it feels like there was a dissonance between what the studio looked like and how he dressed. So the studio doesn’t entirely reflect the artist’s inner state. But still, it was a fascinating experience.

Lesia: And what about a sense of kinship with Bacon? Do you feel his influence in your themes or modes of expression? Or is he simply a prominent figure in 20th-century art?

Anton: He’s with me (or rather, I’m with him) on the same emotional wavelength. I have almost the same vision of the human being and the human place in this world — as a subject of art, as an image. That’s exactly why he’s my favorite artist.

What’s more, Francis Bacon is the only artist I truly hated. When I first saw his works in those Taschen books, I absolutely loathed them. I didn’t even know why. It was something completely different — I hadn’t seen anything like it before, and I didn’t know how to react.

I think that hatred was a kind of defense mechanism. The feeling was so intense that later, I ended up loving him, and he became my favorite artist. From hatred to love is just one step, as they say. And that feeling is unforgettable — that’s how powerful it was.

…What was the question again?

Lesia: About his influence on you overall.

Anton: Bacon can be very influential through his visual approach: locally colored backgrounds and an expressive compositional center. And I, too, fell under that influence.

Lesia: Did your impression of Bacon change after visiting his studio?

Anton: No, it didn’t change. I already had the deepest admiration and the most tender feelings for him. I was in awe — how could it go any further? I just saw the place where he created his works. The studio itself had a strong emotional impact on me. But my attitude toward Bacon didn’t become better or worse. It stayed exactly the same.

Lesia: Who else has influenced you or feels close to you in terms of artistic expression or worldview — among both contemporary and past artists?

Anton: I really love Grayson Perry, the contemporary British artist, Lucian Freud (he's from the same circle as Francis Bacon — and was his friend), Picasso… If I see something useful I can take for myself, I do. But a special place — as you’ve already guessed — belongs to Bacon. I can’t name anyone else on the same level.

I always leaned more toward being a cosmopolitan.

Lesia: By the way, while browsing your Instagram, I saw a photo of you with Frank Wilde — the Berlin stylist known for his selfies in support of Ukraine. How did you meet, and what impression did he leave on you?

Anton: We met in Berlin at an exhibition. He’s gay, and he really liked me. He called me "my sweet pirate." I knew he took those iconic elevator selfies, so I suggested we take a photo together. He invited me to his apartment. He has a lot of extravagant clothing there. We had some drinks, took photos, he told me a bit about his life — and that was it. After that, we only saw each other at official events. And he was always happy to see me. But that was the extent of our acquaintance.

Lesia: Almost every website that features you mentions that you go to Heidelberg in the summer and autumn to paint landscapes. What is it about this place that’s special to you, and why landscapes in particular? And is that even true — or just a bit of repeated info that keeps getting copied everywhere?

Anton: Oh yes, that’s already become a kind of mythology! It’s true, but it wasn’t something regular. Only twice in my life. The thing is, my mother lives in Heidelberg, and I visited her there. One day, I walked past a souvenir shop that sold Heidelberg landscapes. The city has a famous castle and bridge, and all the tourist landscapes depict exactly those.

That shop belonged to an old man from Croatia named Štefan. I went in and told him I was an artist, I needed money, and I could do that kind of work too. He agreed and gave me an assignment. That summer I made a lot of landscapes and sold them. I remember the whole store was covered with my paintings.

I would often drop by the shop, and Štefan would point me out to tourists: “That’s the guy who painted these.” There were Americans — they took pictures with me and my landscapes. They’d buy a piece and snap a photo. So somewhere in the U.S., in some kitchen, I hope, there’s a photo with me in it. It was my little business, because I needed money for a new jacket. I had found a really cool leather one and wanted to buy it. So, nothing too romantic — I just needed money. And I ended up earning more than I needed.

Lesia: That’s great. So, did you buy the jacket?

Anton: I did — and still had money left over. They actually wanted to set me up in that business more seriously and offer me a big commission. I was even supposed to work back in Ukraine, painting landscapes. But I said, “No, thank you. I’m not interested anymore.”

But for some reason everyone decided I go there every summer. No — it was just twice. I needed money, I knew how to paint — what else was I supposed to do? And it’s a touristy place, so that kind of thing was really in demand. It was a good, solid little business.

Lesia: You currently live in Germany. How do you feel the influence of the cultural and social landscapes of Ukraine, Germany, or both?

Anton: What can I say about Germany? It’s a crappy country. Right now, I live in Berlin. And Berlin — it’s just a mess. It’s a place that doesn’t need anything except drugs and parties. There are a lot of galleries, gallerists, exhibitions… but there’s nothing truly interesting. I haven’t dived deep into that scene, but what I’ve seen feels outdated — conceptual art that would’ve been relevant maybe in the 60s or 70s.

I did have some collaborations with gallerists here, but so far I haven’t found anything that feels meaningful — artistically, or in terms of people I could work with or who have something to offer.

Lesia: Is there any symbolism or tradition from Ukrainian culture that feels close to you, and that you’d willingly integrate into your work? You mentioned in a past interview that you’re interested in working with cultural material.

Anton: Yes. But honestly, my work has never included Ukrainian context or symbols. That’s because I mostly worked with European cultural heritage — medieval themes, various underground scenes, naïve art. And I didn’t really want my work to be easily labeled as Ukrainian just because of some affiliation or symbols.

I always leaned more toward being a cosmopolitan. That’s why I didn’t use Ukrainian symbolism or cultural references in my work. But now, in all the projects I’ve done related to the war, of course, they are about Ukraine. But that’s more a product of emotional response. And I focused on more intimate stories — like the one with my grandmother.

Lesia: So, with personal themes?

Anton: To transform war into a deep and meaningful expression, it can only really be done through something intimate and personal — not through factual imagery. For instance, if you paint a bombed-out house, it won’t touch me emotionally, because there are already photographs of that — lots of them.

There’s a photographer, Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, who takes a lot of pictures from the frontlines. His photos affect me much more emotionally than if the same things were shown in a painting. I don’t know why. Most likely, it’s because no one has yet found the key that can unlock that door.

It’s very hard for an artist to depict war. [...] Nothing can go beyond the war itself.

It’s very hard for an artist to depict war. I can’t even name anyone who’s really succeeded… Maybe Otto Dix. But he was directly on the battlefield — he killed people, he saw death. I haven’t seen that, so I can’t tell the story of war in that direct way. I simply can’t create something that exceeds what’s already there — and I’m not even talking about the conceptual side, but the emotional one.

Nothing can go beyond the war itself. I haven’t seen strong examples of how art can truly express this war, maybe precisely because it’s still happening. There’s nothing you can add; physically, it’s impossible to counterbalance it with anything. You’ll only be able to talk about it later, after some time has passed — when there’s been a chance to reflect.

Right now, it’s incredibly difficult to hit the mark. It’s like trying to aim at an animal that’s constantly moving. If you’re a hunter, it’s very hard to hit it, because it’s always in motion, hiding, trying to escape. It’s out of focus, so to speak. And I think that’s exactly what’s happening now.

Lesia: You mentioned feeling signs of a crisis in your work. Have you had similar periods before that you would call creative crises? If so, what helped you overcome them?

Anton: I don’t remember a time when I didn’t have creative crises. In Ukraine, what helped me overcome them was working in the studio and my friends. Here in Berlin, I don’t have that. I can’t even say I really have friends here. There’s no studio, and that makes it much harder. I’m just trying to get through this period. I hope it will get better. Although I know it probably won’t, I still hope. I don’t have a recipe for getting out of a crisis.

Although, actually, new experiences can help a lot. Right now, I’m searching for that myself. It can be a new activity, a new social circle, a new place to go. I don’t currently have the opportunity to do this, but it helps a lot. So I believe the best way out is new experience. Any kind. Something that can push you toward reflection, inspiration… Hate that word.

Lesia: But it keeps coming up.

Anton (smiling): Yes.

Lesia: In what new art genres would you like to work? Maybe you have some ideas?

Anton: I have doubts that art is something I need to continue doing. I don’t even know if I need it at all. I hope so, but right now I don’t see the need for it. I don’t even know what to talk about in this world. Yes, there is a crisis. Is there a way out? I don’t see it yet. But I hope some new experiences will happen in my life and new ideas will appear. Or maybe they won’t.

Lesia: If it’s not a secret, are you working on something right now?

Anton: No, I’m not. The last project I did was recently, in spring. It took me more than half a year. And for now, I’m not doing any creative projects.

Lesia: Do you have any hobbies? Maybe some films that inspire you, or activities, or books? Anything that gives you an inner feeling of calm or satisfaction.

Anton: Nothing gives me an inner feeling of calm. I don’t even remember when that last happened. I’ve been here in this damned Germany for three years and not once have I felt happy. I don’t recall when I was simply content. I don’t know what hobby could help me. I think I don’t even have a hobby. I do some animation work, but that’s not a hobby, because it was a commission, and I was working on a project. Reading? No, I don’t really feel like it right now. Although no, I would like to, but somehow I don’t have the spirit for it now.

It’s a kind of total emptiness, honestly. An emptiness of meanings, an emptiness of being. And it’s unclear if there is anything that can fill this void. We’ll see.

Being an artist, even materially speaking, is not very good, let’s be honest. If you cannot accept that, then think about whether you need this art at all.

Lesia: Maybe audience feedback used to push or motivate you before?

Anton: It still encourages me. But I can’t say that audience feedback has decisive importance. Though it gives my ego and narcissism a boost, it doesn’t create new meanings or ideas. What’s needed is a new experience — and right now I’m searching for it. And when it happens, I hope it will push me toward a new project. So despite my pessimism, I still allow a few notes of optimism.

Lesia: This is wonderful! I hope everything works out for you. So, what question would you like to be asked, but have never been asked, even though you would like to answer it?

Anton (smiling): I’ve never been asked a question about Francis Bacon. Actually, there isn’t any specific question. I’m open to all. No question can upset me.

Lesia: To conclude, I would like to ask: how do you imagine your ideal art project if there were no limitations to its realization? What would you like to create?

Anton: It seems to me that limitations are what bring good results. So, I don’t even know what to say about such an ideal project. I have no idea. And when you’re given everything, you lose focus. Because everything is possible, everything exists. I don’t know what could be done with that. For me, what matters most is what can limit you.

Lesia: Some kind of technical assignment?

Anton: Yes, yes! Maybe then I wouldn’t even be an artist in the sense that I’m fulfilling a technical task. And I do it quite well. But full freedom — I don’t even know… It’s very hard when you have complete freedom.

Lesia: What advice would you give to young artists? Actually, you yourself are a young artist, but to people who are just starting their path in art.

Anton: Young artists, think a thousand times whether you really need this and if you have something to say. God forbid such a path! There are many artists, but not many who truly have something to say. So don’t waste your time if you have nothing. I really advise you to think carefully. Being an artist, even materially speaking, is not very good, let’s be honest. If you cannot accept that, then think about whether you need this art at all. It may turn out you don’t. Think about it, artists!

Lesia: Not very positive…

Anton: This is just how I see it. Everything can be considered positive or negative — it depends on your point of view. Besides, it’s actually quite positive because I’m warning against tragedy. It’s better to think it through because you can waste a lot of time and say nothing in the end.

...another piece of advice for young artists: create meaning, not content.

Lesia: And how would you like to be described in ten years: as an artist, a comic author, a designer, etc.?

Anton: I would like to be described as an artist. Because an artist is not just someone who draws, but someone who creates meanings. And if those meanings are new, even better. So it’s not very important to me what exactly I will be: a designer, a classical artist, or something completely different. The main thing is that I create new meanings. Actually, I hope I’ll still be an artist. But, as I said, an artist is a very broad concept, so I can’t say exactly what kind.

Lesia: Maybe artificial intelligence will really bring some new opportunities for development.

Anton: Or maybe artists will disappear altogether. I don’t even think it’s bad if artists disappear. There is so much content in the world every day. If you can’t create meanings, maybe this place isn’t for you. You won’t be there as an artist — someone else will be. So that’s a small problem. But creating meaning is not something everyone can do. By the way, another piece of advice for young artists: create meaning, not content. Because there’s already enough content, and everyone is tired of it. People want meanings. So, young artists, think about meaning. Or think about whether you need this at all.